What Is PFPS?

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS), also known as runner’s knee, chondromalacia patellae, and patellofemoral joint syndrome, is the most common diagnosis for anterior knee pain around the patella. PFPS is reported by both males and females; however, females are affected more than twice as often as males. Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS) is common in adolescents, athletes, runners and the elderly.

The onset of anterior knee pain is usually gradual. Initially, the most common symptoms associated with PFPS include anterior knee pain that occurs during and after physical activity of sports involving jumping (tennis, football, basketball, skiing, running, etc.) and during bodyweight loading of the lower extremities, such as walking up/down stairs, squatting, kneeling, and sitting with knees flexed. In most cases, there is a clicking or grinding sound when bending the knee. Chronic injury or overuse when an abnormality exists further exacerbates this condition, as well as long car rides or sitting for long periods of time.

Biomechanics of PFPS

Taking a closer look at PFPS reveals the internal structures involved in this condition and their impact on pain felt in the anterior knee. Of particular interest to massage therapists are these major contributing factors of PFPS:

- Lower limb muscle imbalances

- Overuse and repetitive weight-bearing activities

- Arch variations (flat, high)

- Wider hips and knock-knees (Q-angle)

Alignment

Many sports massage therapists support the theory that muscle imbalances may be responsible for poor patella alignment. Normally, the patella moves up and down as well as tilts and rotates through the trochlear groove in the distal femur as the knee flexes and extends. As pressure between the patella and the groove increases, it can become potentially damaging to the cartilage if the patella misaligns to either side of this groove. Over time, this misalignment causes the cartilage to wear down as the patella and the head of the femur rub against one another. Much of the pain associated with this condition is due to the accumulation of inflammatory waste products from the friction, which leads to swelling and further damage to the joint’s synovial lining.

Evaluation

Looking at this condition from a soft tissue point of view, an evaluation of the muscles/fascia from the hip area to the foot should be conducted, with an eye on any associated gait problems. Strong torsional forces travel through the knee during gait. For example, a pronated foot internally rotates the tibia, externally rotates the femur, misaligns the pelvis, and can eventually pull the patella laterally. As a result, soft tissue on the medial side of the knee builds up as the stretch-weakened vastus medialis relies more on the adductor magnus muscle. When running, this type of gait problem would cause the person to land on the lateral portion of the flat foot and roll inward, causing the lower leg to internally rotate. Simultaneously, the vastus lateralis and ITB resist this motion by externally pulling on the lateral side of the patella causing increased friction between the patella and femur.

Of further interest to bodyworkers working with clients with PFPS are shortened quadriceps and hamstring muscles. When working properly, the patella acts as an efficient pulley system between the medial and lateral quads in leg extension and deceleration of leg flexion. However, when massive lateral thigh muscles shorten and fascia thickens due to stress and strain, the medial knee musculature loses the ability to properly track the patella.

Treatment of PFPS

Massage therapy should be included in a comprehensive rehabilitation program that addresses management of PFPS either before or after surgery for debridement of patellofemoral cartilage intended to reduce crepitus and clicking. The treatment goal of the therapist is to eliminate excessive compressive and/or torsional forces at the patellofemoral articulation. Soft tissue methods such as fascial release and friction massage have helped clients with anterior knee pain, with much of the treatment directed to the medial and lateral retinaculum. The retinaculum stabilizes the patella along with the patellofemoral ligaments.

A comprehensive massage protocol for PFPS begins with evaluating the gluteus maximus (superficial) and tensor fasciae latae (TFL), which together become the iliotibial band (ITB), which branches at the knee to the lateral retinaculum, inserting below the lateral epicondyle. Fibrous tissue caused from myofascial adhesions may be palpated assessing for active trigger points in the tensor fascia latae, vastus lateralis, and biceps femoris as well as in the superior lateral aspect of the patella and lateral aspects of the IBT-vastus lateralis border. Palpation of these muscle areas is likely to reveal tender, nodular, restricted areas, tender points, or active trigger points.

Research has found a strong relationship between iliotibial tightness and decreased medial glide of the patella. The ITB can be tested with the Ober’s test. Tight quadriceps muscles, particularly the rectus femoris, can lead to PFPS. Test the rectus femoris by the Thomas test or a prone knee bend. Decreased hamstring length has also been found to be an influencing factor in PFPS. Test the hamstrings via a straight leg raise and look for 80-100 degrees of hip flexion. Other researchers have found a correlation between quadriceps weakness and PFPS. The vastus medialis oblique (VMO), in particular, plays a major role in patellar tracking and should be evaluated for active trigger points.

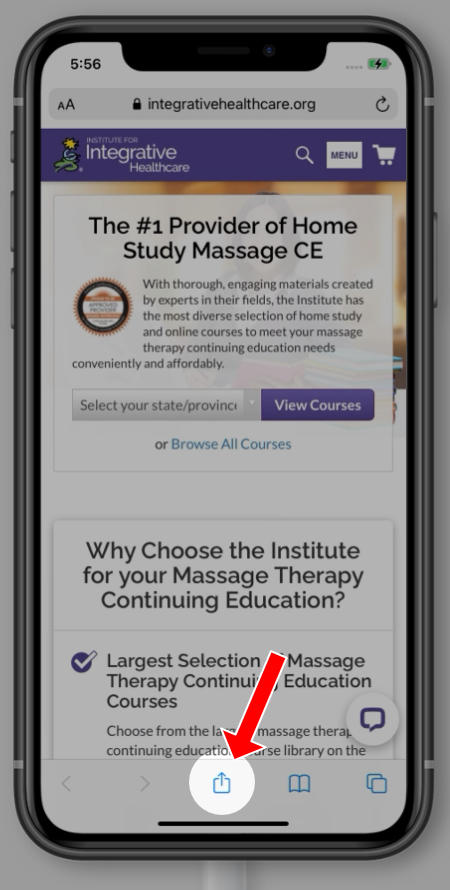

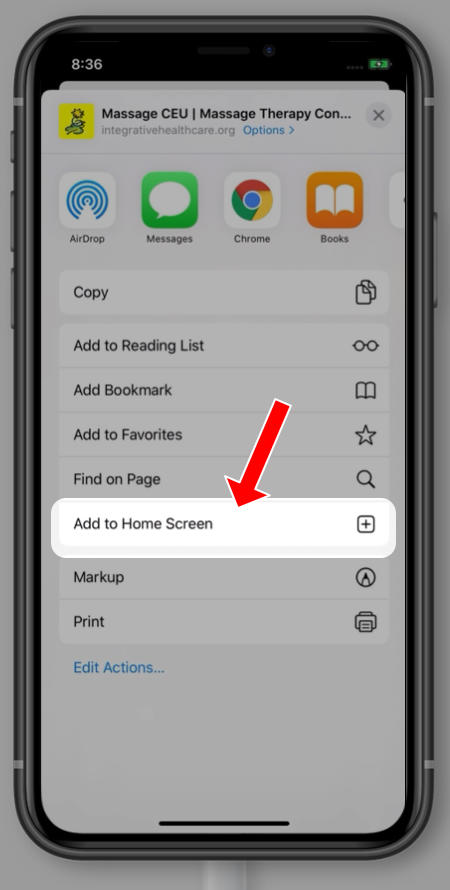

Should there be any inflammation in the knee area, begin with lymphatic drainage prior to proceeding with other massage techniques. Once inflammation has been reduced, proceed with Swedish techniques, including effleurage and petrissage to warm up the gluteus muscles, hamstrings, quadriceps, adductors, TFL, ITB and gastrocnemius and to promote general relaxation. Fibrotic tissue around the patella can be reduced using myofascial release and cross fiber friction followed by ice massage to mitigate any potential inflammatory response to this therapy. Passive range of motion and passive stretches should be performed several times during therapy.

Muscle energy techniques successfully decrease hypertonic musculature and increase the length of the TFL, ITB, vastus medialis oblique, adductors and the hamstring muscle group. Post-isometric relaxation and reciprocal inhibition techniques work best for the hamstring muscle group to reduce flexion contractures and increase range of motion in the knee. Myofascial release is performed to lengthen tissue and normalize hypertonic muscles and fibrous tissue particularly in the TFL, ITB, and vastus lateralis. Neuromuscular techniques can be used to deactivate trigger points in the TFL, ITB, vastus lateralis, and biceps femoris. Tender points identified in the biceps femoris, semitendinosus and/or semimembranosus can be addressed with passive positional release.

Massage was found to be an effective complementary therapy in the rehabilitation of post-ACL reconstruction PFPS (Zalta, 2008). Subjects reported reduced pain levels after massage therapy as well as a significant reduction in flexion contracture. Massage was effective in decreasing the degree of hamstring flexion contracture. Further, self-care exercises and self-massage were given to patients and, when performed regularly during therapy, strengthened the quadriceps.

One last word about contraindications. As with any massage therapy to the legs above the knee, blood clots (Deep Vein Thrombosis) can break off and travel up the bloodstream, resulting in a blocked blood vessel in the lung (pulmonary embolism). During massage therapy, be aware of swelling, pain, discoloration, and abnormally hot skin at the affected area.